Text by Blurbs

Video & photo by Lukas Turcksin

Keytrade and Horst share DIY entrepreneurship as a common denominator. With ‘Their Way’ they inspire their shared philosophy through a content series. ‘Their Way’ offers the stories of DIY entrepreneurs at the forefront of art, architecture and music. We delve into the messy, yet inspiring and insightful process of entrepreneurship. We celebrate and feature compelling stories, challenging initiatives and examples of integrity from around the world.

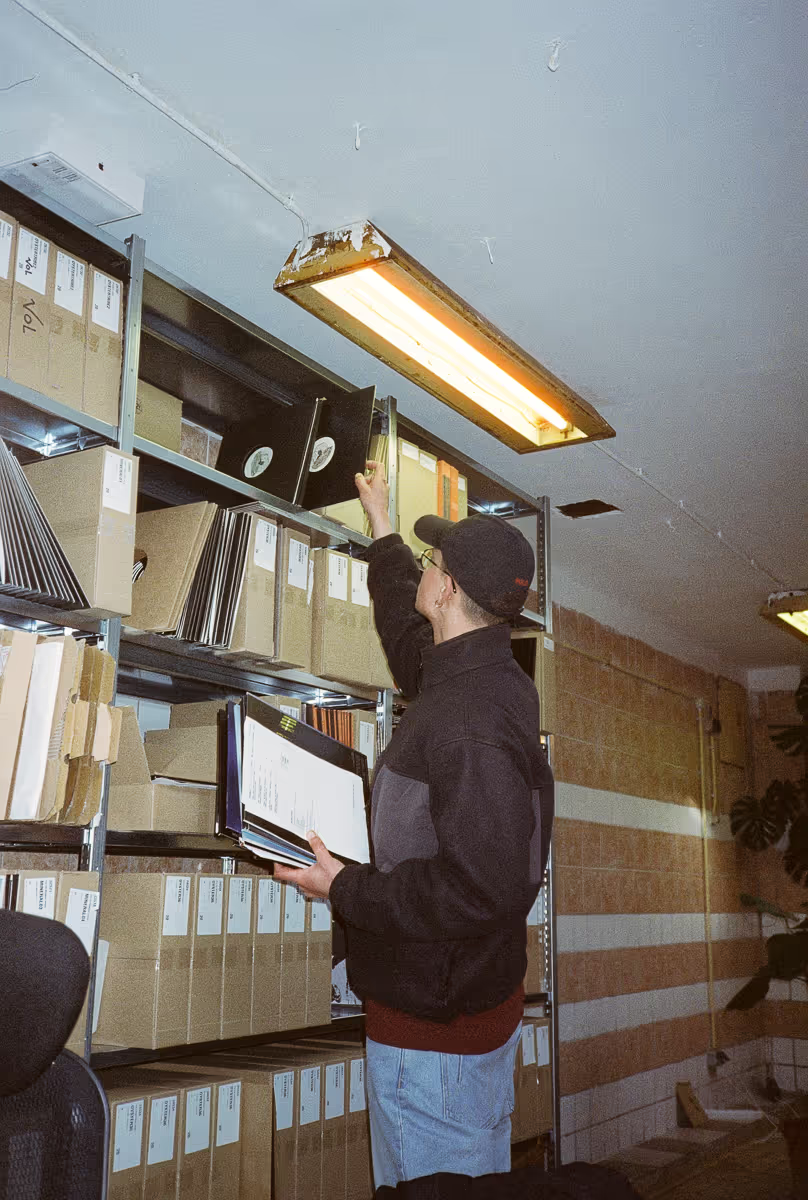

A short ferry ride from the Centraal Station over the IJ and a walk in the sun led us to Amsterdam-Noord, the city’s hive of artsy bars, clubs, and alternative galleries. No surprises then that Colin Volvert chose to set up shop here: packed from floor to ceiling with records and plants, this is where he runs his label Kalahari Oyster Cult as well as the rapidly growing distribution company One Eye Witness alongside Hylke de Graaf. Colin (alias Rey Colino behind the decks) took us through their daily grind, explained how some grisly past experiences shaped his mindful approach to the music business, and gave us some very sound advice about auricular health on the dancefloor.

Horst: Hi Colin! To start off, can you sum up your background?

Colin: I was born and raised in Brussels. While I don’t have a purely musical background, I studied communication science and did statistical analysis of media coverage on electronic music festivals for my thesis, focussing on how media portrayed drug use in that context. For as long as I can remember, I’ve had an acute sensitivity to music: it always deeply resonated with me and moved me in ways nothing else could. These days, I feel blessed to be able to be part of the process where music resonates with others.

I bought my first basic turntables a long time ago, but eventually upgraded to the classic Technics when I moved to Amsterdam in 2016. Around that time, I started working in a record shop and distribution in Amsterdam, alongside Hylke de Graaf. We learnt a lot there about the industry, for better or worse, it eventually led us to starting our own distribution company last year, One Eye Witness.

Horst: Were you more into vinyl than digital when you started out?

Colin: I began with the “vinyl only” thing, firstly because I never had the chance to use CDJs, and secondly because it was at first an easier way for me to process music. These days, I’ve moved away from that because I feel it can be a bit limiting and there’s so many unreleased tracks I want to play/try out. Trying out unreleased music in clubs is a huge part of my process and I must say I missed it during the lockdown. I play a mix of digital and vinyl now, playing older stuff on vinyl or current releases that I really enjoy and forthcoming music. Of course I have a firm attachment to vinyl, but I think that both formats can really coexist together. Take the best of both worlds!

Horst: Is your library very well organized?

Colin: Yes and no! During lockdown, I started to actually get my files sorted, because otherwise it's impossible to deal with so much music. It's tedious but necessary.

{{images-1}}

Horst: Tell us a bit about your record label, Kalahari Oyster Cult.

Colin: I started the label here in Amsterdam in 2017. We didn’t go with “Kalahari” for the geographical reference, it was more of a silly and surreal idea about an impossible cult worshiping oysters in an arid desert, and maybe there is a connotation about rare, hidden gems or pearls that the cult finds. People often say that Kalahari Oyster Cult is a name that is as hard to remember than it is to forget.

Horst: What made you want to launch a label?

Colin: I had found an obscure EP on YouTube, the artist was unknown and I really enjoyed the organic sounds of the 90s Italian Deep House. I reached out to the user to find out what was up and it turned out it was Jacy himself who had produced the tracks and uploaded them. After a bit of bargaining he eventually agreed to release them. From there on, I didn’t really think it through (and it shows) and went with the flow, whilst learning the ins and outs of the business. I have a much more mature approach these days… I think!

Horst: How do you find new music to release?

Colin: That’s the complicated part! When I take on the role of A&R (artists and repertoire), and reach out to people, they sometimes just aren’t interested in releasing on the label. But then as you release more records, you create a network and the more recognition you get and the easier it becomes. When I started, I had no idea what I was going to do but what I'm really keen on now is pushing newcomers as much as I can.

Horst: Do you still meet older, more established producers and go through their archives?

Colin: Yes, especially for our reissue label Mineral Cuts, I have had access to a lot of DAT tapes and archives. It takes a while to go through these enormous amounts of DAT tapes, but I approach it like digging and going through demos. You have to get your hands dirty to find the gold. With one of my previous reissue labels, this whole process was really dry and contractual. There was no human contact involved and that's what I wanted to change when I started Kalahari Oyster Cult, because the “strictly business” approach isn’t really my thing.

Horst: How do you get into contact with artists?

Colin: It all starts with the internet; we exchange music and ideas for an extended period of time, then you get to meet them in real life and hang out or play together! Each artist gives you a huge amount of trust with their music and then you do whatever you can to make it right. This whole process leads to a release that we are all proud of! It binds people, for sure.

Horst: Regarding rereleases and archives, how do you navigate the idea of nostalgia?

Colin: My label is built around nineties sounds, trying to implement nostalgia with a modern sound design. I’m all for innovation in dance music, but there’s also a lot of good stuff from the past, so why not use it? I take great pride in the sound of the records we produce. I mean, I love nineties music, but there are so many records that are unplayable because the pressing sounds too poor. Some say you need to juggle with the way your records sound in order to match them but I think it’s just another unnecessary challenge added. Nowadays, unfortunately, some records still sound pretty flat and I think it’s such a let down when you buy a new record but the pressing/mixing/mastering is poor. It defies the purpose. I hear so many reissues that sound worse than the original and I really struggle to grasp the idea.

{{images-2}}

Horst: You had another label before Kalahari, right?

Colin: I used to run a reissue label back then. I learned a lot about contracts and licensing and it was my first step into the vinyl business. The main thing I got out of this experience is the importance of contracts. Luckily, I was able to reinvest all the knowledge in Kalahari Oyster Cult later. I’ve expanded this philosophy with Mineral Cuts. I see it as curating music: there is one track on one side from an EP and another one of newer things that are favorites of mine. It’s my commercialised dubplate service, if you will. Mineral Cuts has been working really well, which means we get to pay money back to artists rather than someone speculating on Discogs.

Horst: Can you tell us a little bit about speculation on Discogs?

Colin: Well, it's just a silly mixture of capitalism and hype. Discogs is advertised as an online database of information about music, artists, and releases but it’s first and foremost a marketplace. You only need a one time purchase to skew selling prices forever. Our label makes access to music more democratic. So much so that it’s made some people angry! Collectors get frustrated because when you repress a record the original suddenly loses its value before they manage to make a quick buck on it.

Horst: Do you think it’s a bit of a fetish?

Colin: It is, but I must say in any domain whenever there's something to collect and there's too many guys involved, it goes south. So perhaps we need more feminine energy in there, well everywhere really!

Horst: Speaking of feminine energy…Across all of your own labels, your distribution and your role as a line-up curator, how do you deal with equal representation and diversity?

Colin: That's a really good question. I'm fully aware that on the label side there's a huge lack of diversity and I'm actively working on it. Progress is also slow because we're pressing records, which means it takes more than a few months for our actions to be visible. Whereas on lineups, it's pretty straightforward. You can just take action and do it day-by-day! No excuses! I collaborate with Under My Garage for promoting events, and we have these issues in mind when we craft a lineup.

"With our distribution company we are looking to find sustainable ways of pressing. I hope we can open up the conversation on this topic because it’s really crucial."

Horst: Tell us a little more about Oyster Ballads.

Colin: Oyster Ballads is a side-label and a tryout for a more ecological approach to releasing records. I collaborated with Japanese eco-artist Sae Honda who collects detritus off the street and melts it down into a new material. The idea was that the musician, Lawrence Ledoux, would collect plastic garbage and give it to Sae. She then made an original artwork-sleeve from her 'plastiglomerate'.

I tried to make each step more sustainable than a regular release. I wouldn’t say it’s actually sustainable: we have to be careful as there's a lot of greenwashing in the record industry right now. I did my best, which led to the project being insanely expensive, because when taking this “greener” approach everything costs 30 or 40% more.

Horst: How do you think the vinyl industry can be more sustainable?

Colin: With our distribution company, One Eye Witness, we are looking to find sustainable ways of pressing. However, the renewed demand for vinyl means everybody's focused on doing their turnovers right, and pressing as much as they can, so there's no room for discussion about ecology. I hope we can open up the conversation on this topic because it’s really crucial.

Horst: How and why did you start the distribution company, One Eye Witness?

Colin: Covid gave me time to think. I wasn’t happy with the way things were done in my previous job and I wanted to have more control over the distribution of my own records. I reached out to friends and emitted the idea of a new outlet. I think there was a gap for our sounds so we quickly set it up and it became what it is today. It has evolved organically to about a hundred labels! Despite this growth, we try our best to always be available for everyone. What we do most is give advice; even established labels sometimes need reassurance and support.

The other intention was to pay artists properly. This means we make less profit ourselves and we have to put the prices up. We allow smaller labels to take the risk of starting out; we can push labels that wouldn’t be taken by other distributions because they're unknown or too left-field. We support certain projects fully knowing it will be a financial shit show, but it also sometimes takes three releases for the audience to catch on to something artistically crucial.

Horst: Do you ever turn anyone down?

Colin: Yes, firstly because it’s just Hylke and I here, and there are only so many hours in a day! It's also because we only want to do things we think are right. For example, we have had many conversations with labels and artists around cultural appropriation as of late. We don’t ever want to hurt anybody, so whenever we have a doubt about the intent behind it, we simply politely decline.

Horst: Could you describe a typical day at the office?

Colin: We come in, we drink coffee! Hylke deals with the orders on the webshop. We receive deliveries of new records, haul them up the stairs, listen to them and do a quality check. Next, we pack the boxes of records and get them ready to ship out. In the end, we sell to shops, but our job covers the whole process: production, working with somebody for the mastering, the lacquer cutting, the vinyl pressing, the graphic design… then the final product arrives here. We also do digital distribution: tracks are uploaded to a platform and distributed to all the DSPs: Spotify, Apple Music etc.

"It’s not “fast” entertainment: there's a lot of thought from so many people going into these products. People only see the end product or listen to the tracks, but each record requires hundreds of hours’ work."

Horst: We're hearing a lot about healthcare and wellbeing in the club scene. Is that something you feel concerned about?

Colin: Definitely. I recently had an acoustic trauma during my first set at a festival. I didn't think much of it at the time and I then put my earplugs in and went back in to later play the closing set. The next day, I woke up with hyperacusis and tinnitus, so I had to cancel all my gigs for six months. It's an understatement to say that it's been one of toughest periods of my life, and I'm not out of the woods just yet. It's really paradoxical to have something that you love so much turn into something that physically hurts you.

As a DJ I think that you have a responsibility not only towards yourself but also towards the people attending the parties. Since the trauma, I've learned a lot, like it only takes up to 5 minutes for a 105dB noise exposure to become hurtful. The more I talked and advocated about it, the more I realised that everyone knows earplugs exist and can protect you, but few people use them. It's a difficult topic in this industry but God knows that it's dramatic that some 18 years olds step foot in a club for the first time and end up with a life-long and incurable affliction. I'll keep on advocating on the subject, and I was happy to see behaviours change in my close friends in regards to hearing protection. Please, do it before it's too late.

Horst: Did you question the relevance of music and DJ culture over the past few months?

Colin: I had ups and downs during the pandemic, because you can play at home for yourself, but then you miss the purpose of sharing music and the whole cathartic part of it. In the context of the pandemic I was surprised that we managed to launch and sustain a record distribution business, because the things we sell are mostly designed to be played in clubs. There seems to be a new generation of people coming who are eager to buy records. I think we really need music and in the current climate entertainment is extremely important. That said, we keep in mind how we can be conscious about what we do. It’s not “fast” entertainment: there's a lot of thought from so many people going into these products. The amount of hours and conceptualization put into each release is insane! People only see the end product or listen to the tracks, but each record requires hundreds of hours’ work.

Horst: Any last, closing words of wisdom for someone who wants to start out?

Colin: Sign contracts! It's just safer for everyone involved: the label, the distributor, and the artist. It covers everybody's back, and you can be sure that less things can go wrong. Also, a lot of people don't know their rights when they're making or selling music. There’s more than enough resources online, why not take the time to understand it? Finally, protect your ears and others! So that's my main advice: contracts and ear plugs!

.avif)