Interview by Blurbs

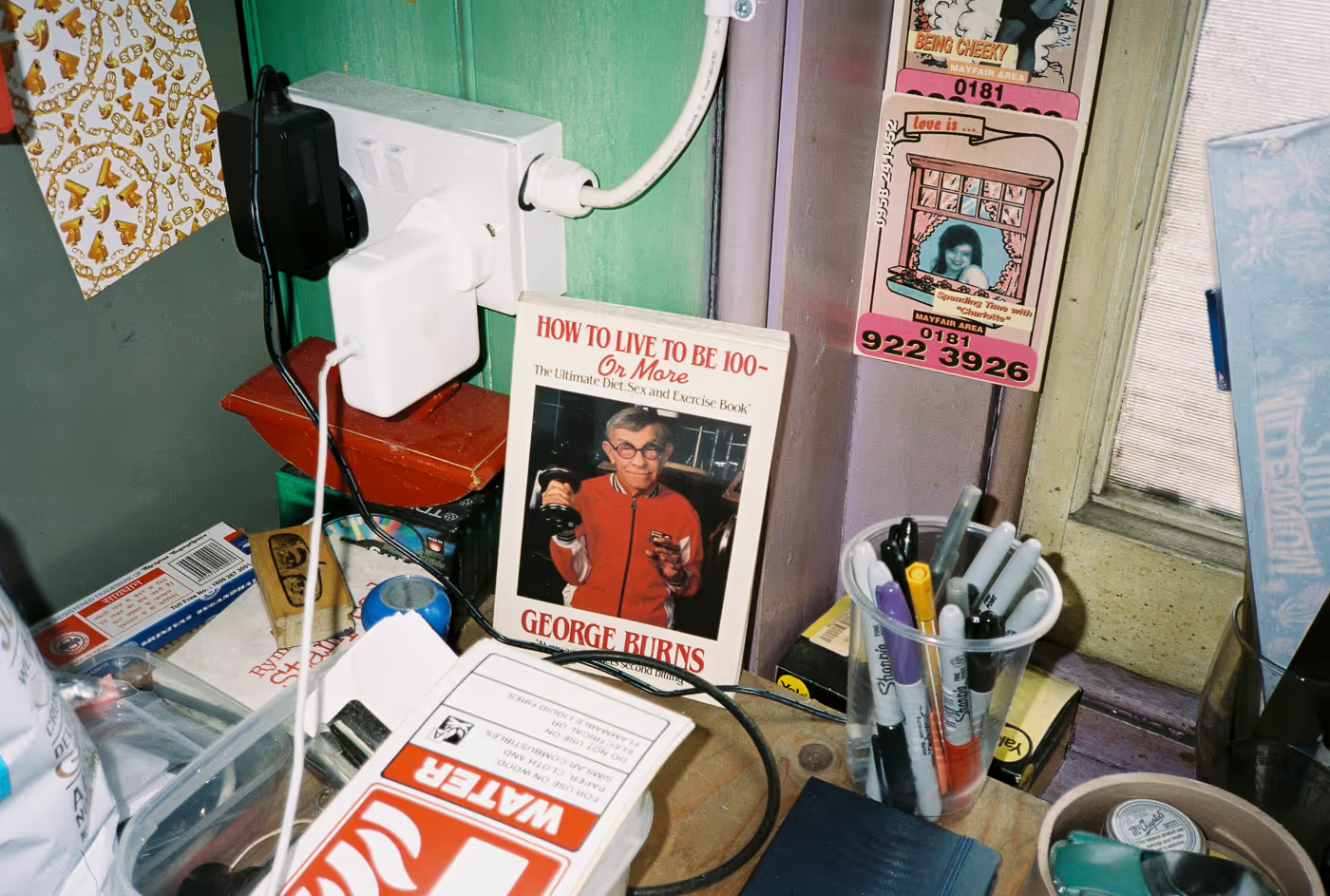

Photo by Lukas Turcksin

Keytrade and Horst share DIY entrepreneurship as a common denominator. With ‘Their Way’ they inspire their shared philosophy through a content series. ‘Their Way’ offers the stories of DIY entrepreneurs at the forefront of art, architecture and music. We delve into the messy, yet inspiring and insightful process of entrepreneurship. We celebrate and feature compelling stories, challenging initiatives and examples of integrity from around the world.

The British conservative Prime Minister Boris Johnson had fortuitously just announced his resignation as we walked towards the Colonnade, a quiet backstreet in London’s Bloomsbury district renowned for its cultural and educational institutions.

Greeted by a banner stating “Save the Horse Hospital” in a stylized punk collage, we knew we had arrived at our destination. Housed in an 18th century hospital for the horses that pulled taxi carriages across the city, this eponymous space is not only an architectural oddity but has also been a haven for countercultures in all shapes and sizes since the late 1970s.

We met with founder Roger K Burton who also runs The Contemporary Wardrobe (a fashion archive and rental service) out of the same building. We went deep on ideas of industriousness, the underground, rebellion, community support, and gentrification, all the while getting insightful glimpses into London’s (counter)cultural past, noting that the same rule seems to apply today: don’t be afraid to go against the grain!

{{images-1}}

Horst: Thanks for welcoming us here at The Horse Hospital, Roger. Could you tell us a bit about your background, which seems rooted in fashion and an interest for counter cultures?

Roger: I was raised on a farm, and left school at 15 to work on another farm and then in a factory. I got really into the "mod" subculture, which meant I needed more money to buy clothes. I was doing odd jobs when my mother decided to sell the farmhouse and everything in it, so I taught myself to restore furniture. I would sell furniture at the market in Leicester, and before long I had a shop!

Clothes became my main thing because they were affordable for everyone.

"Hippie" culture had been integrated into the mainstream, so as a resistance we started to explore the idea of nostalgia for the past and dressing up in old clothes. Much to the horror of my mother, wearing dead men's things! We didn't call it vintage yet, we called it "nostalgia" or "period" clothing.

All of this went very well until the mid-70s when punk broke out and no one wanted nostalgia clothes anymore. We were a little bit too old to be punks, so we started a shop in London called PX that catered for a more “industrial” audience. A good friend of ours who'd opened the first punk club called the Roxy had taken on an empty building in Covent Garden, and offered us the ground floor as a shop. So we shot off to Holland and bought loads of leather coats, and leather jackets, and jodhpurs.

All the stuff we bought was massive, so we had to alter it for the skinny little London kids. We decided we should just kind of use those as prototypes and remake them as garments, which was fine but not really my centre of interest, so I eventually left to continue selling vintage clothes.

Horst: How did you get into more fashion and film work?

Roger: One rainy Saturday in January, this guy approached us on our Portobello Road market stand looking for genuine 60s mod clothing for a film. The film in question was none other than Quadrophenia, one of the first subcultural films about the past. That was my introduction to the film industry. When they had finished shooting, the producers offered to sell us the clothes back. They suggested we start a rental company for film production. Our focus was on postwar teen subcultures, and no one else was offering that apparently.The Contemporary Wardrobe was born.

In parallel, Vivienne Westwood got in touch about a new shop on the King's Road. She had liked what I had done at PX. I had a meeting with her and Malcolm McLaren, and next thing I knew I was building a shop called World’s End. Working with her and Malcolm McLaren was a great experience, because they’re both quite eccentric. In 1981, I did another shop for them called Nostalgia of Mud. We basically built them film sets that were never meant to last.

Later, I was introduced to the film director Julian Temple, who had just finished The Great Rock 'n' Roll Swindle. He asked if I fancied working on music videos, doing the sets and clothing. I had no idea what music videos were, there was no MTV then! Over the next few years I did about 150, 160 music videos. We did Bowie, The Rolling Stones, The Kinks…It was bloody hard work, all day and all night, and fueled on drugs and alcohol, and no sleep…

Horst: What led you to finding this unique space here in central London?

Roger: Following another eviction, I sent one of my assistants to look for potential new places. He came back very excitedly to say that he'd found this empty building, and it looked amazing, and we had to go and see it.The building was in such a state! There were pigeons and rats everywhere. It had been empty for at least 10 years. Half of the roof was missing upstairs. I wasn’t ready to take it on, but the rest of my staff were like, "Oh my God, it's just amazing. We can turn it into the London version of Andy Warhol's Factory!" So it was their enthusiasm and excitement that made it happen. We managed to get a good deal on the lease, and moved The Contemporary Wardrobe here.

Horst: How did you attract people to a place with no obvious storefront, in part of London that wasn’t particularly “cool”?

Roger: We decided to have an exhibition of punk clothing to announce that we had a new space. I approached Vivienne and Malcolm who were a bit perplexed about the idea, but they eventually got behind it and Vivienne lent us a few garments. In the end there was so much of a buzz around the exhibition; it even travelled to a gallery in Tokyo where we had around 15000 visitors!

What could we do next?? Personally, I'd had a long life of going to clubs and being involved in fashion and culture so I thought we could turn it into a little haven for the people who felt a bit left out. That was our guiding punk and DIY ethos. That same year we hosted the graduation show of Chelsea art school students, which later led to us programming interesting exhibitions of marginalised people and their works.

"That made me more determined to make this place a little outpost for people that had nowhere to do or show stuff. It didn't matter what race, colour, or genre they were, they could find a space here and have a home and show their work."

Horst: Were there institutions or spaces or rather a lack thereof that encouraged you to start?

Roger: The institutional lot—the V&A and Museum of London—weren't very challenging in their views or exhibitions. Going back to that first punk exhibition, some curators came from the V&A, pinned me in a corner and said, "You can't show clothes like this. If you want to be a serious space you can't have things that people can touch." Or, "You can't have that sort of lighting because it might fade the garments". Let's not forget this was in '92, or '93, and you could still smoke inside. That evening I think we had 500 people come to the opening, with everyone smoking around the clothes.The institutions were absolutely horrified. For them, things were supposed to be exhibited behind bulletproof glass, and the experience of actually touching stuff was gradually taken away. But we wanted people to experience the shows differently, in an interactive way.

Horst: In the nineties we saw the rise of galleries like White Cube, art fairs like Frieze and movements like the Young British Artists, which all were commercialising and capitalising on contemporary art. How did that impact you and the Horse Hospital?

Roger: Yeah, I was not a fan of that lot at all. In fact, that made me more determined to make this place a little outpost for people that had nowhere to do or show stuff. It didn't matter what race, colour, or genre they were, they could find a space here and have a home and show their work. Having no formal education myself, not having been to university, I was very open to everyone and all their practices.

Horst: Was there ever a red line in the programming or a curatorial theme?

Roger: At that time there were shops and galleries that specialised in certain genres of art or music. But with the Horse Hospital we wanted to be more eclectic; which was a big deal because British people have tunnel-vision. They get into their little subculture or their niche and can't see anything else. It was easy to do an exhibition about tattoo art and have the place filled with tattooed people, but how could we get all kinds of people to cross over?

We decided to start a monthly “Salon”. There was no pressure on anybody to do anything in particular. Basically, we would just open up the space on the third Friday of the month, and if somebody had a bit of work in progress that they wanted to show on the screen, or if somebody wanted to DJ a bit of weird music, or if somebody wanted to do a bit of poetry or dialogue or a performance, they could! This led to people crossing over from the various subcultures and scenes. You'd just look around the room and you'd kind of see every nationality, genre, race. Everyone was chatting together, and it was fantastic. We had doctors, psychiatrists and filmmakers, and performers! We continued down that route. There was no master plan for this space, ever.

Horst: Could you tell us a bit about how things are working today in terms of curating?

Roger: All along, we've had different curators and programmers. One of the last ones was Tai Shani, the Turner Prize award winning artist, and she was here for 10 years. But we also had other curators coming through simultaneously. Coming out of Covid enticing people back into the space has been quite difficult though. Our current exhibitor and artist Chiara Ambrosio came up with this idea of programming something every night, which we never did before. It's been really fabulous. People are really hungry for culture, still.

{{images-2}}

Horst: You were faced with a 333% price hike in 2019. What’s the current situation regarding your lease and the future of The Horse Hospital?

Roger: They've been trying to evict us since the year 2000. My daughter and I started to research the history of the building to see if that could help. There were rumours that it was a horse hospital and eventually we discovered that it really was! There'd been a series of vets here from 1797 through to 1913, then it became a printer's workshop. We managed to get it listed with English Heritage. The owner was apoplectic! Since then, it’s been a constant issue – we either have to give up the lease for a new lease or accept a rent hike of 333%. We managed to negotiate it to an extra ten thousand pounds per year, which was crippling for us, but we had to do it.

Horst: How do you think that rent hikes and people being moved out of their spaces affects culture in London or beyond?

Roger: Well, it just pushes culture out, doesn't it? This has always been the case, there's always been waves of gentrification or economic change. Look at Oxford Street today which is falling apart because of Covid. They will have to reduce the rent for people to go back there. Covid was a really big wake-up call to a lot of property owners. There's office blocks all around here that are empty.

Horst: Do you think that it also leads to artists being more commercial?

Roger: No, not really. I think there'll always be artists and filmmakers that are not interested in being commercial. They're just driven to produce stuff that they want to produce. And people like us are happy to show their work if we can.

Horst: Having recently been threatened to move, and having this huge collection of clothes, what are your views on archiving? Do you see The Contemporary Wardrobe as a recording of an alternative history?

Roger: Yes, of course. We have looked into the museum status side of it. But once again, it's so littered with red tape that I don't think we would be able to operate as a commercial company if it took on museum status. So, I'm looking at alternatives. Asking why can’t we belong to a museum and at the same time be a commercial business? Who writes these laws?

We're just actually going through the Horse Hospital archives now. During Covid, we got funding to have some archive assessors in. And they were great, they spent about a week here and gave us some recommendations, although the main takeaway was that we should do what we want to do with it. I'll give it to somebody at some point, an institution or somewhere that I think that might want it. Or I might even destroy it!

Horst: What's in the Horse Hospital archive, and do you plan to digitise it?

Roger: There is a room upstairs that is just packed to the ceiling with stuff. VHS, magazine articles, flyers, fanzines… at our 20th anniversary, we had this timeline of all our events that went right around the room. It was fascinating seeing people come in, looking for their name or their event amongst the 5,000 artists who have contributed to this space over the years.

We’ve already digitised quite a bit of it. It's all down to money really.

And time. But at the end of the day, it's only a bunch of paper and videos. There's enough waste in the world. I don't want it to be turned into something that it shouldn't be. This place was all about a free spirit and doing stuff the way we wanted to do it. And so I don't want to see it shoved in a storage space somewhere and forgotten about, or become too institutionalised.

Horst: You recently curated the exhibition Hackers : Costumes From the Motion Picture featuring clothing from the film on which you worked as a stylist.

Back in the nineties, what you proposed was a radical mix of genres, and now it's become absorbed as a style. It’s a bit like how Acid house and the appending dress style was a countercultural movement during Thatcherite times, and now it's been watered down and sold on the high street.

Roger: It's a funny one because since the 1970s I've always been trying to stay ahead of the game one way or another. I didn't want to be a hippie so I went for the whole 1950s thing. But as soon as that started to become popular, I had to find something else. Once something becomes popular, it loses its specialness. It’s great that kids are discovering all these old subcultures and movements and reinventing them. But I sometimes wish we could move on a bit! I hope that something new will arise that I’ll still be around to see. I notice little bits of things, but nothing that has any gravitas that really makes you stop and think.

In fact, I'll come back to Vivienne and Malcolm here. They took people on a journey through nostalgia, first with the fifties and then biker culture, and zoot suits. Eventually it all came out in this mish mash of punk clothing that they designed. That was like, oh my God, wow. You could wear a bag if you want to! It was such an expression of freedom. They were totally unique and creative in that respect. I don't feel that now. It was a reaction against hippies and politics of the time. And I would like to see it in the younger generations.

Horst: Is there anything that you could think of that reminds you of that spirit today?

Roger: We had a show here just before Covid by Jenkin van Zyl, they did a residency at the Horse Hospital and integrated items from The Contemporary Wardrobe into their show. They were really into something! Spock ears and massive shoes and crazy outfits that they crafted. They made a great art installation here as part of a programme called Psychic Communities that looked at community building through sensual, sexual, spiritual, embodied forms of connection. I could really see their commitment! I mean, there's plenty of weekend acid house people or proto punks out there. But you rarely see the full timers!

"Every day I used to walk into this building, and every day I’d imagine getting a brown envelope through the letterbox saying, “get out!”. Although it’s not a very nice position to be in, it drove me even more to make every minute worth it."

Horst: Where do you see yourself with the Horse Hospital in five or 10 years’ time?

Roger: That's really difficult. Of course I would like it to carry on! I'm in the later end of my life as it were. I'd like to at least get it all archived properly before I walk away from it. I would never walk away from it completely because I created the damn thing.

Horst: And is there anyone in the team who wants to take it on?

Roger: The archivist and researcher Alexia Marmara is very enthusiastic about carrying it on.

Horst: Are there any other initiatives similar to The Horse Hospital in London or beyond that would like to shout out for the work that they're doing?

Roger: They come and go! There's the October Gallery, which was created by a hippie collective back in the seventies. They bought the building which was an old school, and did exhibitions as a celebration of counterculture, in particular artists and writers like William Burroughs and Kerouac. They’ve managed to keep doing what they do because they became owners of the building back when it was affordable.

Horst: Do you have any advice for anyone who would want to embark upon a journey like yours?

Roger: Be prepared to grab the moment and don’t be afraid to do something that's not necessarily within your remit.

Every day I used to walk into this building, and every day I’d imagine getting a brown envelope through the letterbox saying, “get out!”. Although it’s not a very nice position to be in, it drove me even more to make every minute worth it. For me, it was never about making money, it was just about having a good time with people that were like-minded.